Maroon Lens: Aleem Hossain

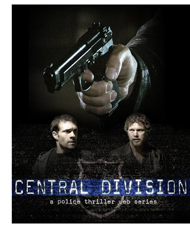

Maroon Lens is a monthly column about alumni filmmakers. First up: Aleem Hossain, AB'00, a UCLA film-school grad who has created a successful online police thriller, Central Division.

The four episodes in Central Division's first season are each no more than four minutes long, and the whole thing takes place in a dimly lit parking garage. And the very first episode ends with a body in the trunk of a car. There are a lot of unanswered questions, but the answers aren't really important—without trying to fit in too much complicated backstory, the filmmakers give us a sense of the two main characters' troubled relationship within the first couple minutes, and the suspense is palpable. Hossain, who's now working working on his first feature film, took some time to answer a few questions about Central Division, which was recently nominated for Best Thriller in the 2010 Indie Intertube Awards.

How did you come up with the idea for Central Division?

When I finished film school in 2004, I tried really hard to get financing for a traditional feature film. It's a long, slow, somewhat frustrating process. A few years went by, and I realized I hadn't directed anything recently. I'd been reading about a few early web shows and so I went out and made my first web series, just a pilot episode really, in 2008. It was a sci-fi show called It Ends Today. I had some success with it—it got me an agent, and the show was optioned by a production company. I was happy enough with the results artistically and career-wise that I decided I should do another web project. I wanted it to be something that was missing from the mainstream TV landscape.

I'd been asking myself, where have all the gritty cop shows gone? Homicide and NYPD Blue were long gone. The Shield and The Wire had ended their runs more recently. Southland had finished a somewhat disastrous (ratings-wise) first season. I've always loved cop shows, so I sat down and started writing. And I immediately started thinking about two actors in particular. Brian Silverman, who was in my UCLA thesis film and Clay Wilcox who was in some films some of my classmates had made. I didn't tell them I was writing for them—I just sprung the finished scripts on them—and they responded within minutes of getting my e-mails.

What about the cop genre drew you in?

The good ones are all about the conflict between principles like truth, fairness, justice, and the realities of the world. It can be really hard to tell stories about stuff like that without being pedantic or boring. But an investigation has such a clear narrative drive that it grounds things. So you can really explore some murky philosophical ideas and confront some difficult topics while still hopefully engaging the viewers.

However, when you've spent much of your life watching cop shows and movies, it can be hard to make one that seems at least somewhat original. When I made Pinkerton, my UCLA thesis film, I knew that I wanted to do a movie about a cop out for revenge—but that storyline seemed so played-out. But then I read this article in the New Yorker where Adam Gopnik was talking about his kid's imaginary friend and I had this thought: what would my childhood imaginary friend think of me now? And even better—what would the childhood imaginary friend of a jaded violent cop have to say to him years later? That's where Pinkerton came from. When it came time to make Central Division, I was excited to experiment in a different way. I hadn't seen any cop dramas in the web-series format. So I gave that a try.

What do you think is wrong with some of the cop shows on TV now?

I don't know if I really want to say that something is wrong with the CSI-type shows, but I can tell you what I don't like. I think they are gross, and they focus on the least dramatic part of criminal investigation: the use of science to gather evidence. I think forensics is a fascinating field, and I'm glad it exists in the real world. But in these shows it's used to arrive at absolute truth in this way that is both unrealistic and uninteresting. I'll take a scene in an interrogation room or a street corner over a lab every time. I'm also just not a fan of really visceral close-up shots of mutilated body organs.

What's your favorite cop show on TV now?

The best cop show currently on TV is Southland. I'm so glad TNT saved that show. If you watch the pilot episode of that show, you'll find everything I love about the genre: compelling and conflicted characters, ethical dilemmas, the struggle to pursue noble goals in a complicated world. And I really have to give the writers, directors, and actors credit—the level of realism in the show is outstanding.

Back to Central Division, what were the most challenging things about creating such short episodes?

The hardest thing is the cliffhangers. I have a love/hate relationship with them, to be honest. I don't know if this makes sense: the cliffhangers are the thing I am the most proud of in the show, but I also often wonder what the show would be like if I'd not used that narrative device at all. Cliffhangers are a big part of most web dramas. And one of the challenges I set for myself was to try and master that convention. It's just that I also have some misgivings about that part of the format.

What was the crew for Central Division?

There were only three main crew people besides myself, all of whom I knew from UCLA. Julie Kirkwood, the cinematographer, had shot a bunch of my classmates' films while I was at UCLA, including my wife's thesis film. And two of my other UCLA friends helped out in all different capacities—rigging lights, holding the boom pole, etc. In post-production, I did the editing, my brother did the main title logo, and a friend of mine did the music.

How did you get the word out about the show?

I think I earned a graduate degree in social networking while promoting Central Division. Twitter and Facebook were huge. I read articles on what time of day to post, how to word tweets, etc. I scoured the Internet for any blog that might want to cover my show and sent the blogger a press release e-mail along with a sneak preview link so they could see the show ahead of the release (which they seemed to appreciate and I think boosted the number of reviews I got). I sent query e-mails to every newspaper and news site I could think of—the traditional news sites ignored me, but the new media ones responded. I networked with other web-series creators. If I saw a show I really liked, I promoted it on my Twitter feed, and the creators often returned the favor. Everyone likes to talk about the amazing opportunities of Internet distribution: the size of the potential audience, how cheap it is. But there are huge downsides too. There's so much noise that it's hard to rise above the static. You can put your show up on a website, but that's very different from getting anybody you don't personally know to watch it.

I was somewhat lucky. I did well enough on my own that a distributor (Koldcast.tv) took notice and picked up the show. They brought in a whole new level of viewership. We got 40,000 views our first month. But in the end, the show never went viral. It never got millions of views. Thankfully, I never thought it would. It's a gritty cop drama—not exactly the bread and butter of the Internet. I'm thrilled at the number of viewers I got, though.

Are you planning to make a season 2?

I have the second-season storyline mapped out, but I'm not sure when I'm going to make it.

Can you tell us about the feature film you're working on?

I'm taking a lot of the lessons I learned from making low-budget Internet projects and trying to piece together an independent feature on nights and weekends. Many of the same people who worked on Central Division are working on it. It's much more experimental than Central Division. We're shooting very spontaneously. If we find a location we like, we work it into the story, etc. Central Division was a pretty commercial project in terms of it's genre and style. I like to switch things up, so this new project is less mainstream. It's an indie sci-fi drama. I hope to finish shooting it before the end of the year.

When can we find out if Central Division wins the Indie Intertube Award?

The winners for that will be announced January 20 via a live web stream. There are some much bigger shows nominated—so I'm gonna stick with "It's an honor just to be nominated" and not get my hopes up.

Ruthie Kott, AM'07