The paper campus

University buildings that never were.

University buildings that never were.

I'm fascinated with things that never were, particularly when it comes to architecture. And particularly architecture from places I'm familiar with—it's fun to play "what if." So when I realized that the University of Chicago Library's Archival Photographic Files had a veritable treasure trove of drawings and models of campus buildings that, for one reason or another, were never constructed, I decided to start an occasional series. In each post I'll delve into the archives to examine some of these buildings that never made it off the drawing board.

First up is the Administration Building. Plans for a dedicated building for the University administration appear to have existed for a while before the Admin Building that we all know and, uh, ignore went up in 1948.

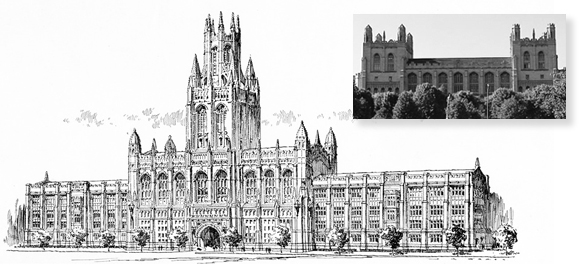

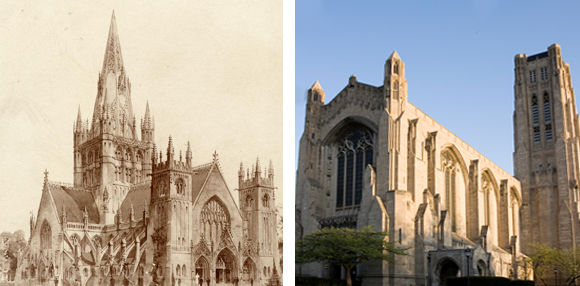

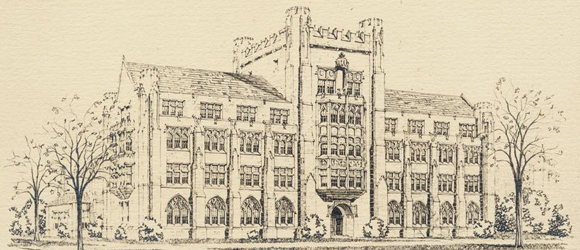

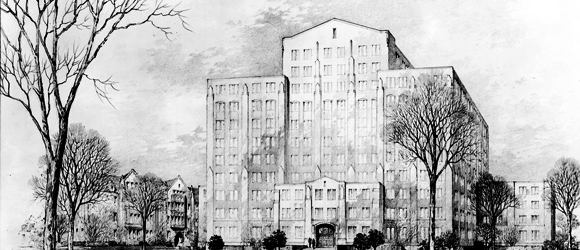

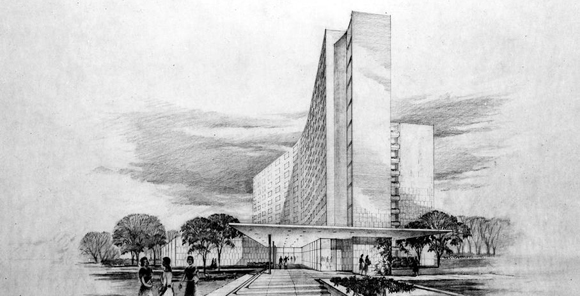

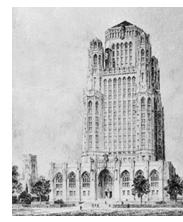

One early proposal (right) was this high-rise Gothic tower, a distant cousin to Tribune Tower or the University of Pittsburgh's Cathedral of Learning!

Judging by the buildings in the background, I'm guessing this would have been roughly where Goodspeed Hall is now. If so, this design might well predate the first classes at the University: Goodspeed was completed in 1892.

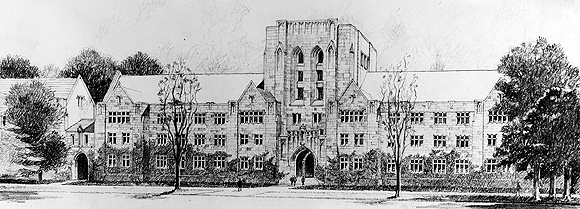

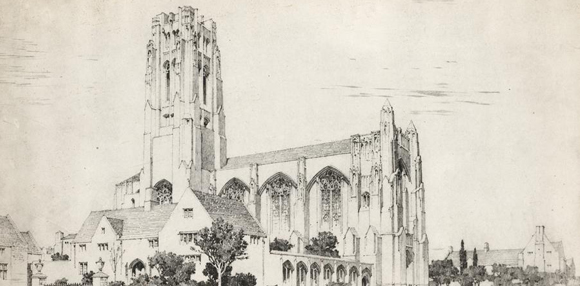

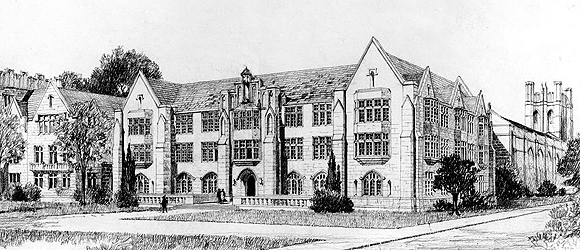

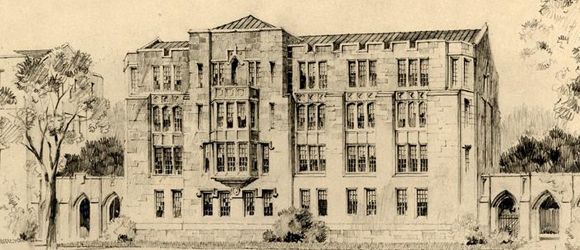

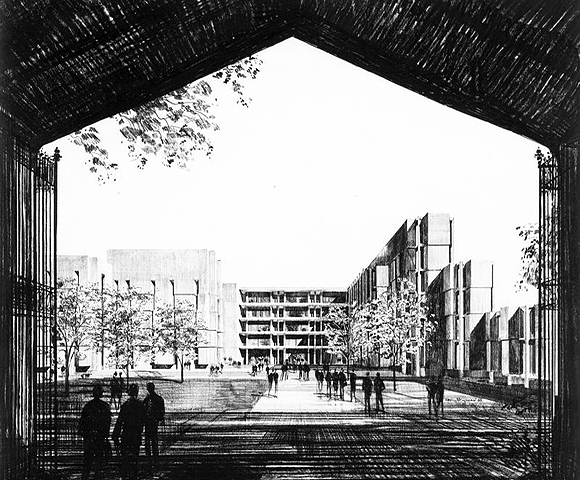

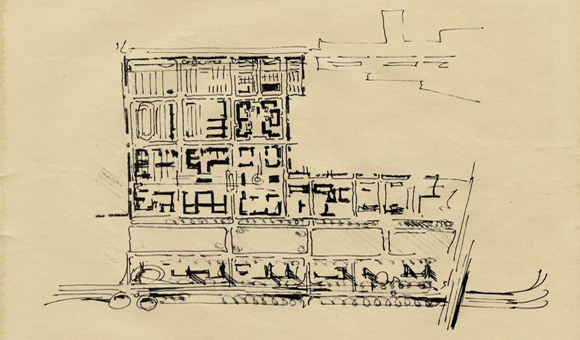

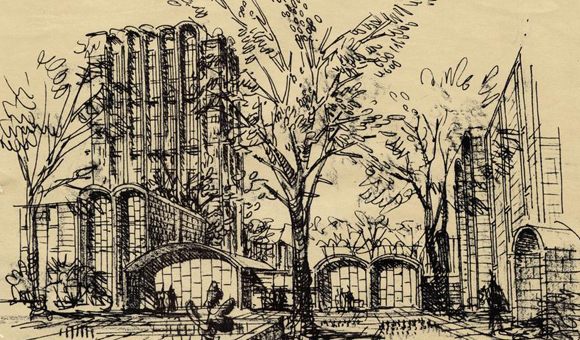

Sticking with the Gothic theme, this proposal (above) would have blended in nicely with the main quads. It isn't obvious from the rendering where this building would have gone, or even from exactly when it dates.

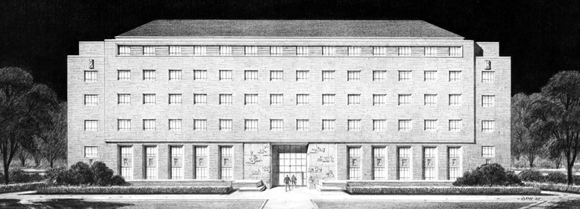

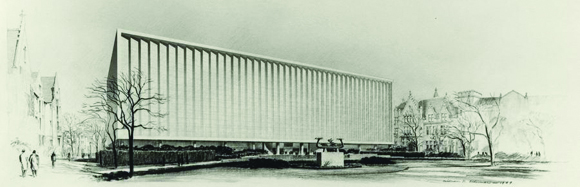

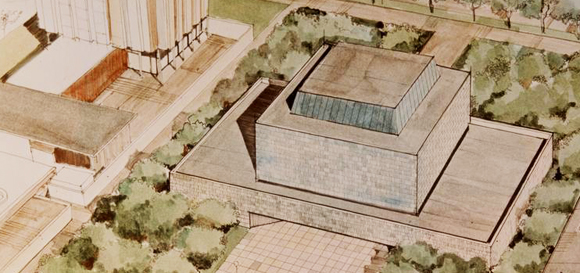

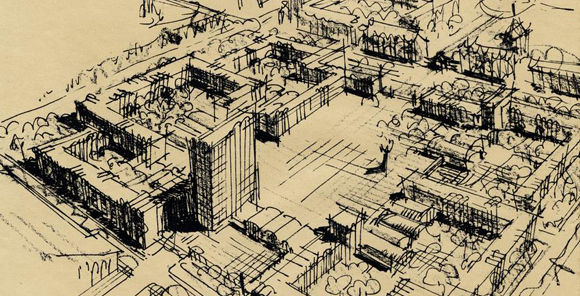

Architectural firm Holabird, Root, & Burgee proposed this design (above) after the Second World War, very close to what was actually built. It's notable for being perhaps the first infusion of modernism into the neo-Gothic main quads.

But this rendering isn't quite as built: note the differences with the final version (above).

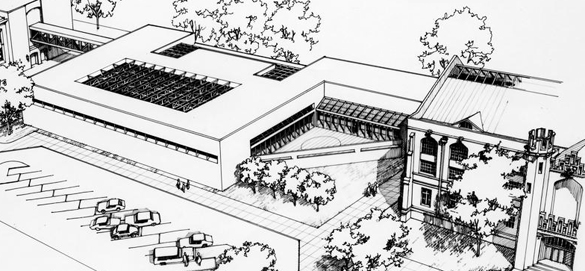

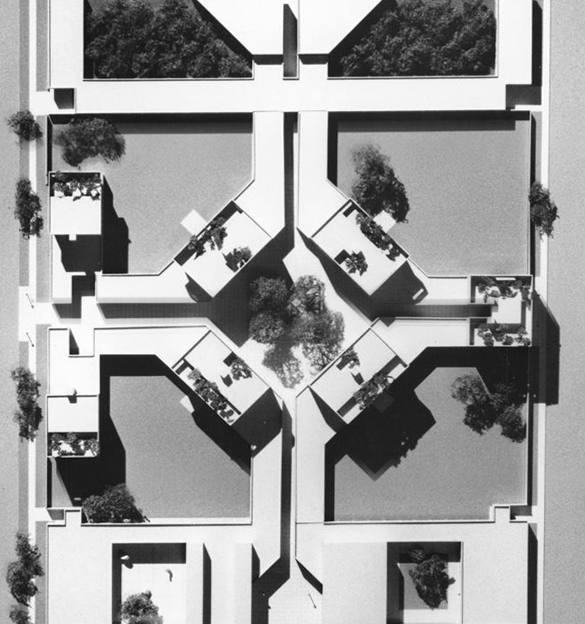

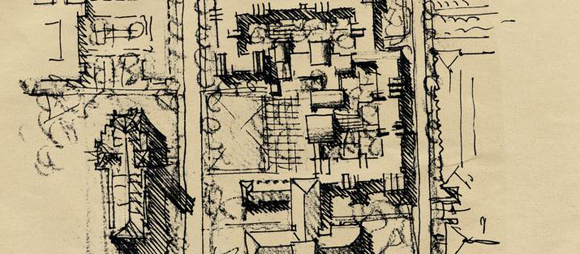

Setting aside Admin, let's go to an old campus favorite—Harper Memorial Library. If you ignore the enormous central tower, this design (below left, top) bears some resemblance to the final product. Note that even at this stage, the third-floor reading room is in place.

I'm not sure why the architect or University settled on the now-iconic twin towers instead of a single spire, but I can't imagine Harper without them.

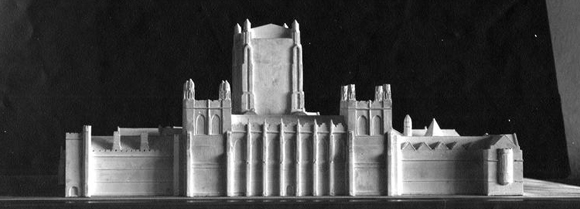

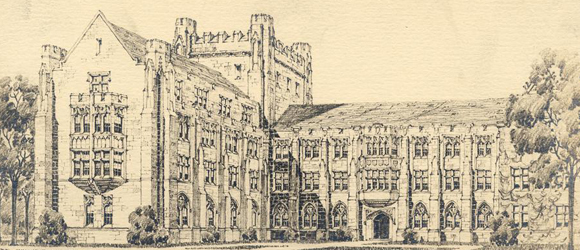

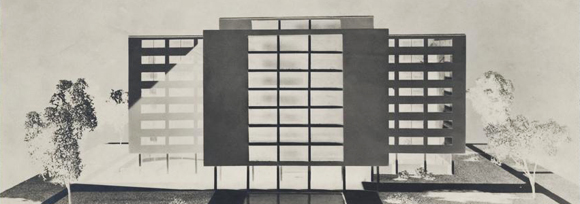

In the 1930s there was a proposal to give Harper more space for books by adding another tower for book stacks onto the side of the building. I'm not sure why this idea fell through, but again, I'm glad. There isn't much detail on this model, but one can only hope those upper stories wouldn't really have been windowless.

Do you have further insight into the history of either of these buildings? Leave a message in the comments.

Benjamin Recchie, AB’03