| Sun | Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

CATEGORIES

RECENT ENTRIES

BLOG ROLL

Sketch-an-etch

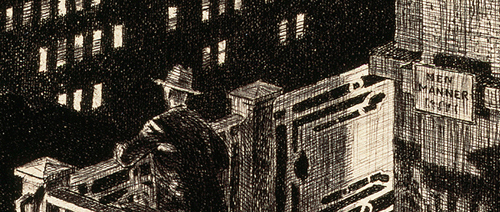

The etching revival of the 1850s and the medium’s early 20th century popularity showed the growing breadth of everyday life. Etchers captured landscapes from pastoral Britain to colonial India, and occupations from trench-bound soldier to lime-burner. The Smart Museum exhibit The "Writing" of Modern Life (through April 19) makes an argument that etching’s range of subjects allowed it to capture modernity’s broad spectrum.

The etching process allowed artists to reproduce individual works. An etcher would quickly draw through wax and expose the metal with a sharp scribe tool, then transfer the image to a metal plate, giving it an acid bath to eat away at the lines. Some artists applied the acid painstakingly with a feather; others would cover the plate entirely.

The exhibit’s variety shows the result of divergent artistic perspectives, in addition to difference in subject matter. Robert Sargent Austin’s The Bell, No. 1 (1926) shows a sharply etched bell in front of a broken wheel, with a richly depicted background. Other artists focus on details of modern architecture like bridges and cathedrals. Some etchings are dramatized; Clare Leighton, who immigrated to New York City from Britain in the early 20th century, made Bread Line, New York (1932), a stark, geometric representation of a crowd suffering beneath advertisements.

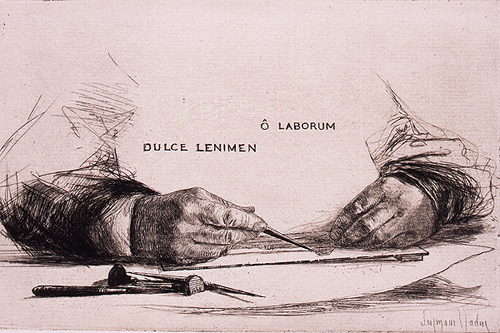

At the height of its revival, etching was regarded as the closest that art could come to writing—each artist had a singular style to transfer the image from mind to the final print. “Among the different modes of expression in the visual arts, etching appears the most literary,” wrote French poet Charles Baudelaire in 1862. According to the exhibit catalogue, an etching was considered tantamount to an artist’s signature, as distinct and identifiable as handwriting.

Rose Schapiro, ’09

Holiday hours: The Smart Museum will be closed on December 24–25 and December 31–January 1. In addition, the Museum will close at 4 p.m. on Thursday, December 18.

Etchings reproduced with permission from The David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art.

December 15, 2008