| Sun | Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

CATEGORIES

RECENT ENTRIES

BLOG ROLL

Intestinal fortitude

It is a truth universally acknowledged that when celebrating someone's 100th birthday, it is not unwise to start a little early. Doctors, especially, know this.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that when celebrating someone's 100th birthday, it is not unwise to start a little early. Doctors, especially, know this.

So on May 29, Joseph B. Kirsner, PhD’42—also known as "GI Joe" and as "Papa Bowel"—will celebrate the prospect of turning 100 with his friends—even though he was born September 21, 1909.

The American Gastroenterological Society is making him jump the gun. So are the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. All these gastro-groups and more will gather in Chicago at the end of May to discuss fecal incontinence, debate the fine points of inflammatory bowel disease, and investigate restaurants during Digestive Disease Week, the "largest and most prestigious meeting in the world for the GI professional."

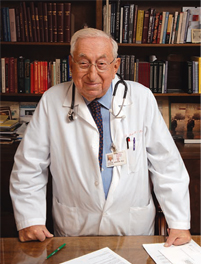

Kirsner, the Louis Block distinguished service professor of medicine, has served on the University’s faculty since 1935. After more than 70 years in practice, he has seen a lot.

During World War II Kirsner was an army doctor in Europe, where he consulted on the difficult issue of refeeding those who had nearly starved in the Nazi concentration camps. Soon after VE Day, he was shipped off the Pacific theater, where he advised on the rehabilitation of more prisoners of war, including a group of Dutch prisoners held captive in Nagasaki by the Japanese army in August 1945, when the second atomic bomb obliterated much of the city.

Tight patient bonds were a hallmark of Kirsner's career. Early on he was recognized "locally and nationally for his successful and compassionate care of patients,” says gastroenterologist James L. Franklin, the author of GI Joe, a 305-page chronicle of Kirsner’s first 100 years distributed by the University of Chicago Press. "The love and devotion his patients felt for him was celebrated and admired." Although he no longer sees patients, they still call him for advice. The key to this lasting connection, says Kirsner, is "competence with compassion."

As competent and compassionate as ever, Kirsner no longer has the energy that enabled him to put in 12-hour days for weeks on end, well beyond the standard retirement age. The problem with turning 100, he says, is "having an active mind trapped in a body that's just too old." He looks forward to his 101st birthday, which he plans to spend "in my office, catching up on the literature."

John Easton, AM'77

May 20, 2009