| Sun | Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

CATEGORIES

RECENT ENTRIES

BLOG ROLL

Once more into the breach, dear friends

In the vast majority of College courses, the most anxiety-provoking assignment is the final paper. But in Consumerism and Popular Culture, taught by Chad Broughton, AM'97, PhD'01, that’s nothing compared to the Breaching Experiment.

In the vast majority of College courses, the most anxiety-provoking assignment is the final paper. But in Consumerism and Popular Culture, taught by Chad Broughton, AM'97, PhD'01, that’s nothing compared to the Breaching Experiment.

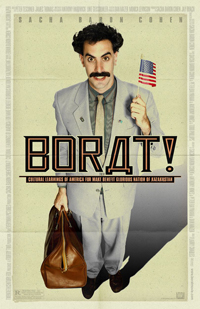

In social psychology, a breaching experiment seeks to understand societal norms by deliberately breaching them. (The film Borat, for example, could be seen as one long breaching experiment.) For Broughton’s course, students choose to violate a norm that has to do with consumerism or commercial society—working alone, in a pair, or (for the particularly nervous) in a group. “Also,” Broughton advises on the assignment sheet, “please avoid arrest or getting you or me in big trouble (a little trouble is fine).”

Below are excerpts from three students’ write-ups of their breaching experiments.

Venti TMI, with ice

I didn’t really want to do this assignment and I’m sure the following write-up will reflect that. I worked with a partner, E., and she suggested that when somebody said, “Hi, how are you doing?” we should respond with TMI (too much information). After some discussion we decided the response should be, “Not good. I just found out I was pregnant and I have no idea who the father is.”

So I walked into the Starbucks in Bronzeville. I stepped up to the cash register, and the man working did not ask me how I was doing. I had to ask him how he was doing, and he finally asked how I was. I gave the agreed-upon response. The guy had a look of shock on his face. “You really have no idea who the father is?”

I said, “No clue, there are just a couple nights I can’t remember what happened.”

He paused a few seconds then asked, “You were drinking?”

I said, “Yeah. It was a party, I was having a good time and you know, one thing led to another.”

Then he asked, “But you know who was at the party right?”

I said, “I guess I should probably make a few phone calls.”

At this point I couldn’t think of anything else to say, so I asked what they had going on in the decaf iced tea department, mentioning I should probably avoid caffeine given my current condition. I settled on a drink, he poured it, I left, and he followed me out. E. had left a minute before I did, and I think the man thought I was trying to distract him while my friend stole something from the store.

Tip off

The breaching experiment I decided on consisted of casually tipping two friends who had helped with small favors. One friend offered to accompany me on a trip to the grocery; on our way back, I acknowledged her company and slipped a dollar bill into her hand. Initially I was surprised when she played along and in an exaggerated, playful voice said, "Thank you," but when I revealed it as an experiment she admitted she had felt both confused and offended. The other friend, a roommate, lent me a key because I pretended to have lost mine. I put the key back in his hand scrunched up with a dollar bill, and to my amusement he immediately and vehemently refused as a puzzled look showed up on his face.

Evidently, I had breached an unspoken social norm—friendships are firmly altruistic. Each friendship is in a sense a tacit acknowledgment of narrow altruism in a wider, stranger world. It’s uncanny to break it.

The customer is always right

I went to a Jamba Juice store downtown and asked to order the unhealthiest smoothie on the menu. The Jamba Juice employee looked at me quizzically. “Our unhealthiest smoothie?” she asked, apparently unsure that she heard me correctly.

And then something completely unexpected happened. “Well, the Peanut Butter Moo’d is probably our unhealthiest smoothie,” she replied. “It’s got chocolate, peanut butter, and frozen yogurt.” And without further incident, she proceeded to make my smoothie.

My request violated social norms because I was choosing a food specifically because it was unhealthy. There were no other criteria. Although the average American eats a lot of unhealthy food, they do not usually choose food specifically because it is unhealthy.

But, after more thought, the reaction of the Jamba Juice employee made sense. American popular culture has enshrined the notion that the customer is always right. If I want an unhealthy smoothie, and Jamba Juice is capable of giving me an unhealthy smoothie, then it better happen!

Carrie Golus, AB'91, AM'93

July 16, 2009