| Sun | Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

CATEGORIES

RECENT ENTRIES

BLOG ROLL

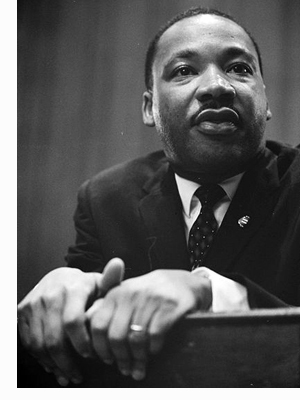

The man who would be King

It occurred to me last Friday, as I sat in Rockefeller Chapel listening to Princeton professor Melissa Harris-Lacewell deliver the keynote speech at the Martin Luther King Jr. Commemoration, that as a 21-year-old I don't know the boundary between Martin Luther King the man and Martin Luther King the institution.

It occurred to me last Friday, as I sat in Rockefeller Chapel listening to Princeton professor Melissa Harris-Lacewell deliver the keynote speech at the Martin Luther King Jr. Commemoration, that as a 21-year-old I don't know the boundary between Martin Luther King the man and Martin Luther King the institution.

For me—and I have to believe the same is true for others who, like me, are too young to have seen Dr. King in the news or in person—this great civil-rights leader has become a symbol. That's not to say his role in our nation's history is in any way diminished; it simply means that, as an American youth, I sometimes struggle to view Dr. King as what he really was: one very human individual fighting for something he believed in.

That's why Harris-Lacewell's speech resonated with me as I sat in the pews last Friday. She told us about Martin Luther King the realist, a practical leader who, in attempting to clear a path for the civil-rights movement, displayed some of the same flaws that every human has. She told us about he marginalized homosexuals during that period, even those who had advised and mentored King. She told us about how he sacrificed certain movements, like that of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, with the idea that such sacrifices would help the civil rights movement as a whole.

But in discussing the practicality of these political moves, Harris-Lacewell's most powerful message was a call to faith, a belief that despite all evidence to the contrary, great things can happen if people continue to believe in them. When King started working toward equality in the 1950s, he was one man striving toward what he believed to be right. As Harris-Lacewell helped us understand, the significance of his efforts was the fact that he did this despite conditions that made equality and justice seem out of reach. The lesson of King and America’s other great civil-rights leaders is that even under the most dire circumstances, great progress can be made, and through the work of flawed people.

Jake Grubman, ’11

January 22, 2010