| Sun | Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

CATEGORIES

RECENT ENTRIES

BLOG ROLL

From surprise to revelation

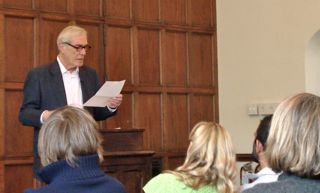

Even after the room was full, people kept coming. They lined the walls, crammed into odd corners, and bumped into each other every time the door squeaked open and another person crept in. Up at the podium, in front of the spot where several students sat cross-legged on the floor, the former poet laureate Mark Strand, looking strong and straight-shouldered just days after his 76th birthday, was reading his poetry aloud:

Even after the room was full, people kept coming. They lined the walls, crammed into odd corners, and bumped into each other every time the door squeaked open and another person crept in. Up at the podium, in front of the spot where several students sat cross-legged on the floor, the former poet laureate Mark Strand, looking strong and straight-shouldered just days after his 76th birthday, was reading his poetry aloud:

I think of the innocent lives

Of people in novels who know they'll die

But not that the novel will end. How different they are

From us. Here, the moon stares dumbly down,

Through scattered clouds, onto the sleeping town,

And the wind rounds up the fallen leaves,

And somebody—namely me—deep in his chair,

Riffles the pages left, knowing there's not

Much time for the man and woman in the rented room,

For the red light over the door, for the iris

Tossing its shadow against the wall...

Occasionally Strand looked up to smile and take in a few faces, but mostly he seemed apart, pleasantly and politely focused elsewhere. A former professor in the Committee on Social Thought who now teaches at Columbia University, Strand is one of the country's most famous living poets and Chicago's current Sherry poet-in-residence. On April 21 he gave an hour-long reading in Classics 110.

I had an English professor in college who told us never to miss the chance to hear poets read their own work. Listening to them, she said, you can pick up things that no amount of analysis will teach: intangible evidence of how a poem works, how the parts move together, and how an idea arises from that motion. In the years since then, I've listened to Mark Strand read half a dozen times (more by coincidence than design) and every time, I hear something in the poetry that I might never have seen in the printed lines. What struck me this time was the contrast between his poems' evanescent, fantastical meanderings—into dreams and waking visions, into Death's living room, onto the riverbank where Orpheus wept and sang and died, into a foreign land with a singing man and camel—and the concrete, even emphatic, endings those poems often have. Introducing Strand, Chicago poetry scholar Richard Strier noted his "measured, circuitous stalking of the subject, turning surprise to revelation." Strand's poetry is both substantial and insubstantial, surreal and sharply real.

After 50 minutes or so of reading, unperturbed by the listeners shuffling in and the buses wheezing past on 59th Street, Strand looked at his watch, glanced up at the wine and cheese waiting on the table at the back, and promised one more poem before the reception. "Actually, it's more like a song," he said. "More like a song written by a Spanish poet in, say, 1925." He paused. "Maybe García Lorca." Then he read:

Black fly, black fly

Why have you come

Is it my shirt

My new white shirt

With buttons of bone

Is it my suit

My dark blue suit

Is it because

I lie here alone

Under a willow

Cold as stone

Black fly, black fly

How good you are

To come to me now

How good you are

To visit me here

Black fly, black fly

To wish me good bye.

Lydia Gibson

April 30, 2010