| Sun | Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

CATEGORIES

RECENT ENTRIES

BLOG ROLL

Proof of faith

Nina Burleigh, AM’87, was amused when she first heard about what Israeli authorities called the “fraud of the century,” a forged limestone box that was believed to have been the first evidence of Jesus’s existence. Reading the New York Times “from cover to cover” while procrastinating writing her book Mirage: Napoleon's Scientists and the Unveiling of Egypt (Harper, 2007), Burleigh, a journalist, was drawn to the story about four antiquities dealers and collectors who had been arrested for “taking real artifacts and altering them to make them more valuable and appear to relate” to biblical tales and characters. It was late 2004, soon after the presidential election that was a blow to people of her “political persuasion.”

Nina Burleigh, AM’87, was amused when she first heard about what Israeli authorities called the “fraud of the century,” a forged limestone box that was believed to have been the first evidence of Jesus’s existence. Reading the New York Times “from cover to cover” while procrastinating writing her book Mirage: Napoleon's Scientists and the Unveiling of Egypt (Harper, 2007), Burleigh, a journalist, was drawn to the story about four antiquities dealers and collectors who had been arrested for “taking real artifacts and altering them to make them more valuable and appear to relate” to biblical tales and characters. It was late 2004, soon after the presidential election that was a blow to people of her “political persuasion.”

“One group credited with the reelection were the evangelical Christians,” Burleigh told an Oriental Institute audience in early March, and she read the Times article trying to imagine the kind of person who would try to fool believers. “I have to admit that my original motive was to amuse myself, I guess, by thinking about this.”

Her imagination--and months of research--led to a 2008 book, Unholy Business: A True Tale of Faith, Greed and Forgery in the Holy Land (HarperCollins), about the world of biblical archaeology and its contradictions. Archaeologists are the "natural enemies" of dealers and collectors, said Burleigh, who make money off people willing to pay for something that can be considered biblical proof. People of faith travel to the Holy Land in droves, she said, to visit John the Baptist's cave or the Jordan River, where John was said to have baptized Jesus. There, they can rent white garments and wade in the water. The tourist economy, said Burleigh, is a reason why looting and forgery is such a problem in biblical archaeology.

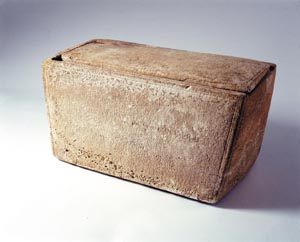

The limestone box, called the James Ossuary (of unknown provenance), was announced to the public in 2002 at a press conference cohosted by the Discovery Channel and the Biblical Archaeology Society. Inscribed with the words, "James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus" in Aramaic, the ossuary had belonged to well-known Israeli antiquities collector Oded Golan. Many scholars who knew Golan didn't trust him, Burleigh said, because they knew he often bought looted artifacts. But still the ossuary was exhibited at Canada's Royal Ontario Museum for a couple months in 2002-3.

Eventually the Israeli Antiquities Authority (IAA)--a tiny, underfunded government agency responsible for protecting some 30,000 archaeological sites in Israel--claimed that the box was a forgery, discovered through an analysis of the patina, a film that builds up on an object naturally over time. After further investigation, IAA officials believed that Golan had made other forgeries as well, and he was one of the four arrested in 2004.

The trial is still going on today, and Burleigh believes that Golan is probably going to get off. The problem is that the prosecution put a lot of archaeologists on the stand who are not used to being "grilled by the most expensive lawyers in Tel Aviv." They've never had to defend their work within the constraints of a courtroom. What might look like compelling evidence to one archaeologist--like writing dated to a particular time period--could be shut down by another expert who claimed that, for example, the length of the leg on a particular letter signified an earlier time period. There's no compelling evidence on either side.

Many people still believe that the James Ossuary is real. Evangelicals, said Burleigh, are not interested in what those who suspect forgery have to say. And even with scholarly work, she said, it's hard to find disinterested biblical archaeologists. "Faith and science--they work together here. In the end, it really is what you believe."

Ruthie Kott, AM'07

April 21, 2010