| Sun | Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

CATEGORIES

RECENT ENTRIES

BLOG ROLL

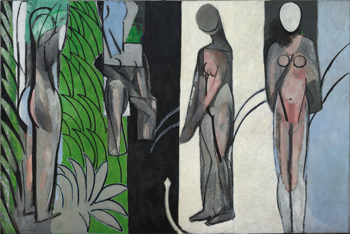

Deep Matisse

A curator and her team go below the surface to make new discoveries about the French painter and sculptor.

If you think that languid nudes and colorful cutouts define the work of Henri Matisse, think again. The exhibition "Matisse: Radical Invention, 1913-1917" reveals a surprising and pivotal period in the artist’s career. Stephanie D’Alessandro, AM’90, PhD’97, co-curated the show at the Art Institute of Chicago, which critics have called "thrilling," "spectacular," and "easily as demanding as it is intelligent." D’Alessandro spoke to UChiBLOGo about the project in a May interview.

How did the Matisse exhibition come about?

How did the Matisse exhibition come about?

I’ve been at the Art Institute since 1998, and we hadn’t had a modern European painting or sculpture exhibition for some time. As a modernist, I knew this was something I wanted to do, and Matisse was a logical candidate. Early on, I began to think about our painting Bathers by a River, which ultimately was the origin of inspiration for this exhibition. In 1909 one of Matisse’s great patrons—a Russian collector named Shchukin—asked the artist to make two decorative panels for the staircase of his home in Moscow. The two paintings that were finished for that commission were Dance II and Music. But many scholars have suggested that Bathers by a River was somehow related to them.

What happened next?

Around 2005 we took Bathers by a River down from the galleries and started to do some initial research that then led to a longer study. That meant going back to the files, pulling all the historical documents together, and surveying the literature. Also, every work in the exhibition was subjected to a very detailed study in the conservation lab where we looked at X-rays; we looked at the painting with infrared reflectography, which is a kind of camera that allows you to see under-drawing, like the very early sketch of something. We also looked at the paintings with high-powered microscopes. Then I brought all the information that existed at that time, and with a conservator from our team plus someone at the Museum of Modern Art, we looked at the work together. As we began to look at a group of works, there was a new body of growing information about how Matisse began changing the compositions and how he produced them. It was eye-opening.

What do you hope this show will contribute?

In the past, scholars have often pointed to this period, 1913-17, as one of the most ambitious for Matisse, one of the most experimental. I think that what this exhibition offers is a very close understanding of what that really means. There are beautiful paintings in this exhibition and in the catalog that have been marveled at over the years, but they’ve seemed like anomalies within Matisse’s career. I hope that people will agree that because of the new research we’ve been able to do to suggest the chronology and the timeline of his progress—as well as to dig in deeply to how these things were made—we can appreciate how Matisse executed this grand transition and how the works relate to each other. I think we can now see a very deep connection between this period of time and the rest of Matisse’s career.

Do you ever sneak into the galleries to see how visitors are reacting to the show?

I try to go in the galleries as much as I can to look at the paintings, and I always see things that I didn’t see before. It’s a joy to have worked so hard on something with great personal delight, but it’s also wonderful to walk into the exhibition and see so many people there. It just makes you feel like it was worth it.

You had a lot of help with this project.

My colleague John Elderfield at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and I worked really hard on the idea. The research was executed by a team of conservators, curators, technicians, and researchers from the Art Institute and MoMA. It wasn’t just art history that led the effort, or science, or technology, or conservation. It was each of these things mutually reinforcing the others.

You’ve said that curating a major exhibition is like doing a PhD. How?

An exhibition of this scale and intellectual and curatorial intention is very much like doing the research for and writing a dissertation. The only added part was imagining how to present it visually on walls, instead of just with a book. You have to make it a visual experience, sell it to the public, and make it understandable and interesting in a different way. It gets very intense, but if you like this kind of work, it’s the thing that you live for.

"Matisse: Radical Invention, 1913-1917," runs at the Art Institute of Chicago until June 20 and at the Museum of Modern Art in New York from July 18 to October 11.

Elizabeth Station

June 2, 2010