| Sun | Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

CATEGORIES

RECENT ENTRIES

BLOG ROLL

Checking out history books

Mansueto may be the shiniest of our libraries, but a look through the archives reveals some surprising facts about other collections when they were new.

I’ve heard it called the Librodome and the Egg, the Greenhouse and the Blister, but only time will tell how we’ll be talking about the brand new Joe and Rika Mansueto Library in a decade or two. And while the reception of the new library will certainly be different from those that already populate campus (never was there a HarperCam during its construction) it’s impossible to tell now what will stand out about the library in the future. But, thankfully, there’s a long history of placing a premium on the stored word—the second appointment President Harper made to the new University was of an assistant librarian: Mrs. Zella Allen Dixson in July 1891. (The first appointment was of a Latin professor, which I’m sure seemed urgent at the time.)

I’ve heard it called the Librodome and the Egg, the Greenhouse and the Blister, but only time will tell how we’ll be talking about the brand new Joe and Rika Mansueto Library in a decade or two. And while the reception of the new library will certainly be different from those that already populate campus (never was there a HarperCam during its construction) it’s impossible to tell now what will stand out about the library in the future. But, thankfully, there’s a long history of placing a premium on the stored word—the second appointment President Harper made to the new University was of an assistant librarian: Mrs. Zella Allen Dixson in July 1891. (The first appointment was of a Latin professor, which I’m sure seemed urgent at the time.)

In that historical spirit, I decided to take a look through the Magazine archives to see what stood out about our libraries when they were built.

Harper Memorial Library was completed in 1912, to the great relief of everyone involved—before that it shared space with the University Press and the gymnasia (one for men, another for women) in a one-story brick building on the site of today’s Hutch Courtyard. It was full of high-tech gadgets, at least by the standards of its day: a Magazine contributor extols “electric book-lifts," “pneumatic tubes for the conveyance of book orders and charge-cards," and “speaking tubes and telephones which facilitate viva voce communication.” Real Flash Gordon stuff, if you ask me. And history really is cyclical—the massive Automated Storage and Retrieval System in Mansueto is a simply a modern, scarier version of that book-lift technology. (Maybe soon robots can read my Derrida?) Fun fact: apparently the University of Chicago seal is carved in six places around Harper. Can you find them?

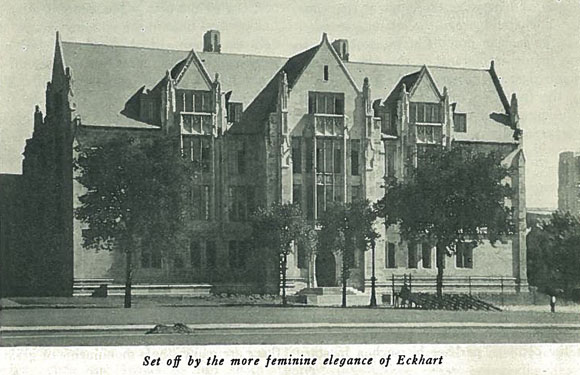

Eckhart Library was built in 1930 amid a flurry of construction projects across campus for $725,000 (about $9.5 million today). At the time, Eckhart was seen as more modern-looking than the blockish Cobb and Ryerson Halls: according to a July-August 1931 Magazine article by art instructor Hugh S. Morrison, “[they] seem slightly old-fashioned now, rather bald in their lack of refinements; but the masonery is sound, and they have a bold picturesqueness of mass often lacking in the newer buildings. Perhaps the best of them is Ryerson Laboratory, now set off in all its ruggedness by the more feminine elegance of Eckhart.” I can’t imagine what the author would think of Mansueto if limestone Eckhart is the picture of airy femininity—to put it in 1930s terms, it’s a future much more Buck Rogers than Metropolis.

The D’Angelo Law Library, and the new law quadrangle it accompanied, were ushered in with a year of celebration and high-level recognition: a Supreme Court justice, British nobles and ministers, and Vice President Nixon all spoke at the ceremonies. But for all the fanfare, D’Angelo’s opening was overshadowed in the Magazine by a three-page article profiling the U of C Parapsychology Society in anticipation of a contest with Cambridge University.

The School of Social Service Administration (SSA) Library moved from Cobb Hall, the oldest building on campus, to the newest, a Mies van der Rohe steel-and-glass enclosure housing classrooms, offices, and research rooms for the School. This must have come as a shock to the faculty used to working in a block of limestone—I wonder how Regenstein staff in Mansueto will feel about unfettered access to the sky.

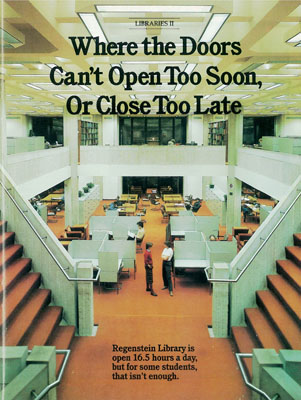

The inimitable Regenstein Library. Much was made of its location on the old Stagg Field, a symbolic gesture of academic supremacy noted in the Magazine in mythical proportions: “In the winter of 1969-1970, the destruction crews came in and the Stagg Field wall came tumbling down, to reveal, full-fledged from the head of Zeus, the new Regenstein library.” Whether you see it as a masterpiece or an eyesore, the Reg is the most massive building on campus. Much of the discussion surrounding the library's completion in 1970 was not simply about its brutalist architecture but the monumental task of moving two million books in the space of two months. Originally the senior architect for the project wanted to place the new library smack in the middle of the main quadrangle, which would have made it possible for some committed students never to cross 57th Street. Originally each floor had its own color of wall-to-wall carpeting: the first floor was gold, the second and third orange, the fourth green. “I feel a sense of elation when I enter in the morning,” one librarian said.

Crerar Library, the newest collection on campus, was built in 1984 as part of the new science quadrangle. A Maroon editorial fretted that the new quad would split up the undergraduate student body between science and humanities majors, but it seems that the absolute silence in Crerar draws like-minded agoraphobes from across the academic spectrum. Originally established downtown in 1894, the library was founded with very specific instructions from benefactor John Crerar. “I desire the building to be tasteful, substantial, and fireproof,” he wrote in his will. “I desire the books and periodicals selected with a view to create and sustain a healthy moral and Christian sentiment in the community, and that all nastiness and immorality be excluded. I do not mean by this that there shall not be anything but hymn books and sermons, but I mean that dirty French novels and all skeptical trash and works of questionable moral tone shall never be found in the Library.” If I ever find a dirty French novel in your library, Mr. Crerar, I'll be sure to let you know.

And so we return to our futuristic bubble, the Mansueto Library, and students such as myself look forward to many hours of solitary and communal misery inside the transparent belly of the beast. While it might have fewer gargoyles than its predecessors, a bold, expensive, titanic book cellar sure says University of Chicago to me.

Burke Frank, ’11

July 14, 2010