| Sun | Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

CATEGORIES

RECENT ENTRIES

BLOG ROLL

The book that dare not speak its name

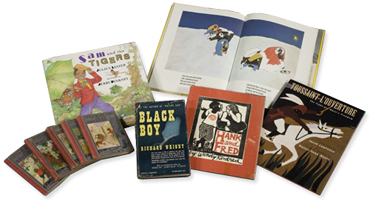

Barbara and Bill Yoffee's (AB'52) gift of African American and children's literature provides new resources for research.

“A blog on Little Black Sambo,” I said, when a colleague asked what I was working on. I watched his eyes widen, and stay wide, as I babbled on, trying to contain the damage, “...it’s actually a really important donation to Special Collections, all these different editions of Little Black Sambo.” He nodded but looked unconvinced. Great, I thought. Now he thinks I’m a racist.

“A blog on Little Black Sambo,” I said, when a colleague asked what I was working on. I watched his eyes widen, and stay wide, as I babbled on, trying to contain the damage, “...it’s actually a really important donation to Special Collections, all these different editions of Little Black Sambo.” He nodded but looked unconvinced. Great, I thought. Now he thinks I’m a racist.

“There is very little to say about the story of Little Black Sambo,” reads the preface to the first American edition (1900) which, thanks to the generosity of donors Barbara and Bill Yoffee, AB’52, I was able to hold in my hand. The preface explains that “an English lady in India, where black children abound and tigers are everyday affairs” had written and illustrated the story for her two young daughters during a long train journey.

Of course, there is plenty to say, or at least ask, about Little Black Sambo. As a start, why is it so widely considered racist? And if it’s racist, why is it still so popular?

“It’s a story that children love,” says Alice Schreyer, director of Special Collections, “a classic children’s story.” In the original (if you have forgotten the details, as I had) Sambo gets a new outfit: a Red Coat, Blue Trousers, a Green Umbrella, and “a lovely little Pair of Purple Shoes with Crimson Soles and Crimson Linings,” in Helen Bannerman’s quirky capitalization. “And then wasn’t Little Black Sambo grand?”

But as he walks through the jungle, Sambo has to give away his fine clothing, piece by piece, to four tigers so they won’t eat him; he manages to persuade them to take even the seemingly useless shoes (“You could wear them on your ears.”) and the umbrella (“You could tie a knot on your tail, and carry it that way.”). The tigers then fight over the clothes, chasing each other around a tree so quickly that they turn into melted butter (What? OK, it’s a kid’s story). Sambo’s father scoops up the butter, his mother fries pancakes in it, and Sambo “eats a Hundred and Sixty-nine, because he was so hungry.” The End.

Awesome! Or not. Well, first there’s the name “Sambo,” which was “already in opprobrious use in the United States,” says Schreyer. Then there are Bannerman’s odd illustrations, which seem to reflect the influence of American racist imagery. But Bannerman, who was untrained, had never been to the States. Would she have seen racist drawings somehow? Would she have seen a minstrel show?

Despite Bannerman’s primitive illustrations (like many children’s authors of the time, she was just a parent desperate to amuse her kids), Little Black Sambo, published in England in 1899, was immediately popular. As the Yoffee collection shows, the story was adapted over and over again, with different words as well as different pictures. “The illustrations became increasingly stereotypical and harsh,” says Schreyer. “It became incendiary.”

But the most recent books in the collection take the opposite approach. Two versions, both published in 1996, attempt to sanitize the story in fascinatingly different ways. The Story of Little Babaji returns to Bannerman’s original words, superfluous capitals and all. But the illustrations, by Fred Marcellino, portray Indian characters, while the somewhat defensive “Note on the Text” points out, “The Story of Little Black Sambo... clearly takes place in India, with its tigers and ‘ghi’ (or melted butter),” so the characters have been given “authentic Indian names.”

Then there is Sam and the Tigers, written by Julius Lester and illustrated by Jerry Pinckney. As he perused more than 50 versions of Little Black Sambo, Pinckney writes in the introduction, “I struggled hard to find my own approach to right the wrongs of the original and several subsequent versions”—a process he found “liberating.” In this adaptation, the little boy, Sam, lives in Sam-sam-sa-mara. The characters are African American, the clothing from the 1920s, the language slangy: “Ain’t I fine,” Sam declares.

Both The Story of Little Babaji and Sam and the Tigers are sincere and well-intentioned. And both somehow just don’t succeed. It’s almost as hard to look at them as it is to look at the original.

The Yoffee collection includes nearly 1,000 works of children’s and African American literature—and a lot of it can make you feel pretty uncomfortable. Next year the collection will be available for researchers in literature, history, African American studies, gender studies, sociology, but the collection hasn’t been completely processed yet. I feel like I haven’t completely processed it yet either.

Carrie Golus, AB'91, AM'93

August 9, 2010