| Sun | Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

CATEGORIES

RECENT ENTRIES

BLOG ROLL

Pictures from an excavation

In central Turkey, OI faculty and staff help get to the bottom of a puzzling ruin.

“The great expanse of ruins, once teeming with life and resounding with the voices of a powerful people who dominated most of Asia Minor, now lies mute and barren.” So wrote archaeologist H. H. van der Osten in 1926 about Kerkenes Dag, the low mountain in Turkey where a vast city once stood. Those who had seen the ruin couldn’t agree on its age, so James Henry Breasted asked his colleague Erich Schmidt, who was stationed nearby codirecting the Oriental Institute’s Hittite Survey, to look more closely.

Schmidt’s succinct wire back, “kerkenes posthittite preclassical + schmidt,” confirmed that the city belonged to the late Iron Age—not a period of immediate interest to the OI expedition. That was the end of any serious digging at Kerkenes for seven decades.

Fast-forward to 1993, when Geoffrey and Françoise Summers of Middle East Technical University launched a new excavation that soon drew researchers affiliated with the OI. Scott Branting, AM’96, then a Chicago master’s student in Hittitology and Anatolian Archaeology, wound up writing his dissertation on the city plan at Kerkenes. Today Branting is a codirector of the excavation as well as director of the OI’s Center for Ancient Middle Eastern Landscapes (CAMEL) and assistant research professor.

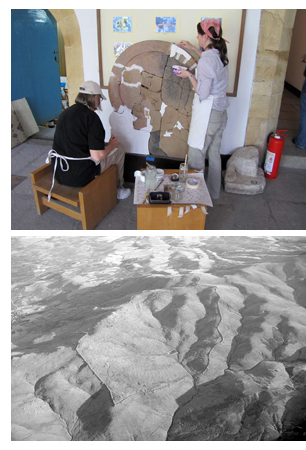

Last summer Branting and assistant conservator Alison Whyte spent time working at Kerkenes. When they returned, they fielded questions about the significance of the site and the role of conservators at an excavation.

What do we know about the city on Kerkenes Dag?

Scott Branting: The city has been tentatively identified as the mysterious city of Pteria, mentioned by the Greek historian Herodotus. If it was Pteria, it was built around 600 or 610 BC and was likely destroyed in 547 BC by King Croesus of Lydia. If not, it might date somewhat earlier, but a lot of our material points to the same range.

What else have you learned from the objects you’ve found there?

Scott Branting: The objects we know something about tend to be Phrygian—the people King Midas belonged to. The pottery and the inscriptions, for instance, have many Phrygian features. But there are also strange, crazy objects that don’t have parallels anywhere else. There seems to be some experimentation that was going on.

How do you explain that?

Scott Branting: In a city of this size, there might have been many different types of people coming together. This is a time when a lot of the older empires of the Near East were collapsing, so craftsmen may have been moving around, looking for somewhere to go. You may end up with a multicultural city where people are experimenting and trying out strange, serendipitous things. Some of the large stone objects we’ve found are just without parallels anywhere.

What’s the larger historical significance of all this?

Scott Branting: For a long time it was thought that the Phrygians went into decline during this period and became part of the larger Lydian Empire. When Kerkenes was found, we suddenly had this massive city further off to the east that apparently is largely Phyrgian. It’s a little bit of a puzzle, frankly.

From a codirector’s perspective, how does having conservators onsite help you?

Scott Branting: They’re responsible for daily excavation of very fragile materials. When something is very fragile, it’s removed together with all the dirt surrounding it and taken to the lab, where a conservator like Alison can finish excavating it under more controlled conditions. In 1996, one ivory plaque looked interesting and important enough in the field that we lifted out the whole block, and discovered in the lab that it had gold leaf and a carved frieze on the other side—it was really quite amazing.

What do you enjoy most about working on-site at a dig like Kerkenes?

Alison Whyte: It’s interesting and exciting to see an object freshly excavated. At the museum, I work on many objects that have been glued together or received some other treatment in the past. I’m working on a ceramic now that was probably glued together in the 1930s or ’40s and, because the adhesive has deteriorated over time, it has to be redone. It’s nice to have something you can start off fresh with. I also love the opportunity to travel and the experience of working in an area of Turkey that’s pretty much off the tourist’s path.

What are the challenges?

Alison Whyte: You suddenly find yourself having to think about certain logistics that you take for granted at home. Things like: where am I going to get water? Will there be electricity, and, if so, what’s the current? How reliable will it be? What supplies will be available? Excavations are often in very remote areas, and it’s rarely possible to get everything you need locally. So I bring a lot of what I think I’ll need (adhesives, other chemicals, microscopes etc) with me. We’re lucky at Kerkenes that we have a building more or less dedicated to conservation that has water and electricity, but it’s not always the case. I have to think in advance of everything I may need and how I’m going to get it to the lab. This is a particular challenge because with an archaeological excavation, you never really know what’s going to come out of the ground.

Laura Demanski, AM'94

Photos courtesy Scott Branting.

September 17, 2010