| Sun | Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

CATEGORIES

RECENT ENTRIES

BLOG ROLL

Cloning terror

We have met the enemy, says literary scholar W. J. T. Mitchell, and he is uncanny.

We have met the enemy, says literary scholar W. J. T. Mitchell, and he is uncanny.

The so-called "war on terror," a legacy of the Bush administration, no longer grabs front-page headlines. But the phrase and the conflict are "a fact of life,” says scholar and critic W. J. T. Mitchell, and whether we’re paying attention or not, both are part of our present reality.

In a recent Humanities Day lecture, Mitchell sifted through some of the verbal and visual images that the war on terror created—and that created the war. His latest book, Cloning Terror: The War of Images, 9–11 to the Present (due out next month from the University of Chicago Press), does the same.

Mitchell’s talk analyzed the war on terror through the lens of the “uncanny,” a literary concept explored by Sigmund Freud in a 1919 essay. In fiction, the uncanny evokes dread, terror, and disgust; it blurs reality and fantasy; it uses ghostly doubles and repetition to conjure confusion and doubt.

Before and after 9/11, the Bush administration used the same strategies to advance its science and foreign-policy agendas, says Mitchell. Fear of new technologies, for example, prompted resistance to cloning, “and many lumped it in a category with stem-cell research, abortion, homosexuality, and other evils.” Administration officials and the media depicted jihadists as nameless, faceless, clones, prompting dread of evil-doers.

The administration’s major coup was to make the metaphorical war on terror a reality by invading Afghanistan and Iraq. “This is the central example of the moment of transition in the historical uncanny,” says Mitchell, “when something we thought was only fantasy, only a metaphor, is made literal because someone has the power to do it.“

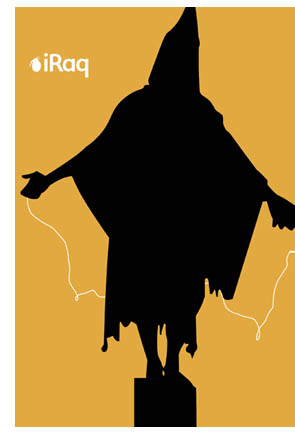

Training his gaze on the torture of prisoners at Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison, Mitchell gave a lengthy analysis of the image of a hooded prisoner with outstretched arms connected to electrical wires. The photo has been widely circulated, partly because of its “uncanny resemblance” to Christian iconography: “This is supposed to be the figure of the terrorist captured and brought to justice,” says Mitchell. “Instead it turns into a kind of composite of Christ welcoming–Christ mocked, wearing a blindfold; or Christ resurrected; or the ecce homo (‘behold the man’) with Christ standing on a pedestal.”

Mitchell’s talent lies in dissecting facts that we take for granted but which should rile us to the core, and asking disturbing questions about issues we don’t often pause to consider. Why, for example, were the rank-and-file soldiers who took and appeared in photos at Abu Ghraib the only people ever charged with abuse? Why has the Obama administration quietly retired the phrase “Global War on Terror” but continued many of its strategies under the aegis of “overseas contingency operations”?

And why should we examine recent history in terms of the uncanny? “We live in a country in which our politics are dictated by amnesia, by forgetting who did what, by taking the emotions of the moment and elevating them into political causes,” Mitchell says. “The period we have just come through is a great example.”

“My aim is to do what historians always do: remember the past so that we will not have to repeat it. Our enemy is the uncanny.”

Elizabeth Station

November 3, 2010