| Sun | Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

CATEGORIES

RECENT ENTRIES

BLOG ROLL

Waiting for super-cops

In South Africa, public fear of violence feeds a popular obsession with crime.

By Elizabeth Station

“Our ideas about crime cannot be separated from our idea of truth,” anthropologist Jean Comaroff argued in this year's Ryerson Lecture. In contemporary South Africa, many citizens believe that the country has turned into “a Hobbesian war zone.” Post-apartheid, said Comaroff, there is the widespread conviction, “especially among whites and the new black middle class, that policing is ineffective, that an economy of violence and corruption has taken root, that civil and moral order can no longer be presumed.”

“Our ideas about crime cannot be separated from our idea of truth,” anthropologist Jean Comaroff argued in this year's Ryerson Lecture. In contemporary South Africa, many citizens believe that the country has turned into “a Hobbesian war zone.” Post-apartheid, said Comaroff, there is the widespread conviction, “especially among whites and the new black middle class, that policing is ineffective, that an economy of violence and corruption has taken root, that civil and moral order can no longer be presumed.”

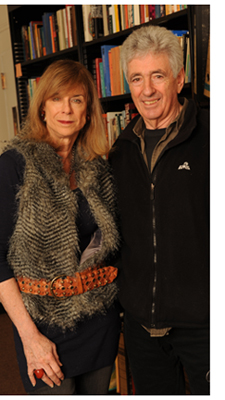

Comaroff based her remarks on The Truth About Crime, a book-in-progress that explores South Africans’ fixation with crime and detection in both their personal lives and public culture. She is coauthoring the study with her husband, John Comaroff; both are distinguished professors of anthropology who divide their time between Chicago and the University of Cape Town.

“South Africa exhibits high rates of lawlessness, to be sure,” Comaroff told listeners in Max Palevsky Auditorium. Yet statistically, violent crime kills fewer South Africans than do AIDS, heart disease, and car accidents. Stoked by sensational headlines, blaring car alarms, and TV crime shows, the public’s fear of rape and murder is disproportionate to risk. “South Africans are captivated by images of law and disorder, the more dire the better,” she said. “Many remain convinced that democracy has, with tragic irony, deprived them of their basic right to safety and protection.”

As anxiety grows, citizens have also embraced unconventional crime fighters and policing techniques. "Diviner-detective” and police colonel “Donker” Jonker, for example, created an occult-related crimes unit in 1992 to investigate homicides stemming from witchcraft. Next came the Scorpions, a now-defunct, FBI-trained police force that investigated smuggling and government corruption and staged televised raids on the homes of African National Congress politicians like Jacob Zuma. In the rural northwest—far from the national spotlight—the Comaroffs studied a case in which local police investigated a poor family’s complaint of assault by a tokoloshe, which, “as all South Africans know, is a squat, hairy, witch's familiar." Police didn’t solve the crime, but they called on both the media and a prophet-healer to help.

Such cases “bespeak a loss of trust in the will or the capacity of the state to enforce order,” Comaroff argued. Yet South Africa is not the only place where the public is obsessed with crime and detection—or where “the complex interplay of the state and the market has rendered authority ambiguous, inscrutable, ghostly.” In present-day Egypt—and previously, in post-socialist Central Europe and nascent Latin American democracies—political change ushered in "periods of moral ambiguity, legal uncertainty, and social disorder," said Comaroff. "In this light, South Africa is decidedly unexceptional."

The super-cop, or diviner-detective, "may be an apt embodiment of the paradoxes of law, order, and sovereignty in places and times rapidly outrunning the logos of modernity," she concluded. "But this figure also personifies a persisting faith in the possibility of a legible world."

May 26, 2011