| Sun | Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

CATEGORIES

RECENT ENTRIES

BLOG ROLL

Reel volunteers

A night in the life of a Doc Films projectionist.

By Mitchell Kohles, '12

I remember watching Fight Club as a 16-year-old and first understanding how movies made it up onto the big screen. Or thinking I understood. It wasn’t until volunteering at Doc that I learned projection involves more than watching the upper right-hand corner of the screen for “cigarette burns.”

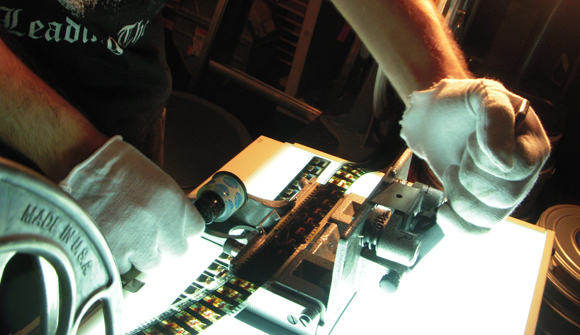

Unless you’re Tyler Durden, this isn’t the fun part: transferring the film onto show reels, rewinding the film, checking and repairing splices, and adding our own if necessary, noting the scenes where dots (those cigarette burns) appear to indicate the end of the reel, determining the print's proper sound format and aspect ratio.

Doc is dedicated to passing these skills on to new volunteers, and I let my APs do this prep work while I look over their shoulder or tend to the projectors. Hopefully, after three quarters of working under different projectionists, an AP will take the projectionist exam to become a PJ, running his or her own show the following quarter.

For 35mm film, we use a changeover system with two projectors, affectionately named Evelyn and Wanda for their east/west location. When the show starts, the film will run through Evelyn until the reel is almost empty—about 20 minutes. Eight seconds before the end of the reel, the dots will appear in the screen's corner for an eighth of a second–four frames-and I'll turn on Wanda’s motor and raise the douser to let the light flood into the chamber. In the print's final second, as the film is running through Wanda, a second dot will appear, and I'll step on the changeover pedal to project Wanda’s image instead of Evelyn’s, which is now just black filler, the reel’s “tail.” If everything goes well, the audience doesn’t notice a thing.

When my APs confirm the film’s aspect ratio, I swap out Evelyn and Wanda’s lenses for the correct ones. I also rub the film gate down with a 50-50 alcohol–water solution we call “the mix” and shoot pressurized air into the chamber to clear any loose dust. Before most shows, it is only necessary to clean the components that touch the film. The cool thing is that hardly any of the film actually touches the projector: despite looping through locks and clamps and pulleys, the film is mostly guided along by rotating wheels with sprockets that engage the film's perforations and prevent any significant transfer of dirt or grime. I try to perform this simple maintenance before each show, although the real cleaning is left to the equipment chair.

Of course, a screening doesn’t always run smoothly. Projectionists have nightmares about the bubbling, deep-colored metastasis on screen that signals a burning print inside the projector. Though not all mistakes in the booth have such inflammatory results. If a film breaks below the sound chamber, the outgoing film will spill onto the floor in huge ribbons while the projector continues to show the print on screen. A PJ can recover from this film spill if he is quick and cool-headed enough to find the broken end of the print, reattach it to a new takeup reel, replace the original reel with the new one, guide the spilt film back onto this new reel, and allow the stronger tension of the takeup motor to catch up to the film still running through the projector. All this can be done without stopping the show or alerting the audience. That’s the fun part.

Of course, this sort of stunt would only be done if the screening were more important than the print—we would never risk damaging a rare or archival print by letting it spill out onto the floor. In that case, it's better to just stop the show.

As a profession, projectionists’ numbers have been dwindling ever since the xenon bulb was introduced in the ‘60s. We became even more expendable when a new reel system that used platters was introduced in the ‘70s. Platters are used by most multiplex cinemas today: all the film is placed onto one giant reel–thereby avoiding the changeover process–and fed through the cinema so that the same print runs through several projectors and appears on several screens. That’s why Green Lantern will be showing at 6:00 and 6:15––it takes 15 minutes for the print to travel from one projector to the next. A multiplex can handle 12 or more screenings in a night with just one projectionist.

We don’t do that at Doc (remember Evelyn and Wanda?). We prep the print of Hitchcock or Brakhage, and we usually show it only once or twice before shipping it back to the distributor. The labor-intensive changeover system allows us to project films from archives that demand the more gentle system. On the other hand, most of us aren't pros. “As a volunteer-based student organization that puts a lot of emphasis on teaching people how to project film, Doc is not exactly at the top of the list of groups to lend fragile and valuable prints to,” explains Andrea Nishi, ’13, co-general chair of Doc.

Still, our changeover system makes us more attractive to film depositories than a platter house is. Kyle Westphal, AB‘07, former Doc programming chair and head projectionist at the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York, describes the tradeoff in an interview with the San Francisco Film Festival: “There are good reasons for such policies—namely that it forces the projectionist to actually be there during the screening and maintain the integrity of the print by not cutting and re-splicing it at heads and tails of every reel." There are upsides to platters too. "In some ways, platter projection extends the life of a print; a film opens at a multiplex, and it stays there for weeks. It screens dozens of times, but because it's all built up, there's less handling involved, less wear and tear and random damage in that each reel isn't rewound and threaded over and over every day."

The film industry is changing, and as distribution goes digital and film repositories become more selective about who they lend to, Doc’s commitment to showing original prints on physical media has become increasingly difficult and expensive. In May 2010 volunteers and board members (also volunteers) gathered to discuss how Doc would address the changes. Some proposed hiring full-time projectionists, cutting the volunteer staff nearly in half. Others proposed establishing an “office manager” position to maintain relations with distributors and handle Doc’s finances. Becca Hall, AB’10, a former Doc volunteer and cofounder of the Northwest Chicago Film Society, attended the conference and describes Doc’s predicament: “Basically, Doc presently operates as if it's still the 16mm era, when films were available to anyone and striking new prints was easy—and when the equipment used was simple enough for a schoolteacher to use and maintain. All this puts the possibility of Doc continuing to exist as we've known it in serious jeopardy.”

As part of the University community for more than 75 years, Doc proudly holds the title of longest-running student-operated film society in the country. As I watch my APs thread the 35mm film into the projector, I can only hope we don’t give that up.

July 22, 2011