| Sun | Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

CATEGORIES

RECENT ENTRIES

BLOG ROLL

Print and politics

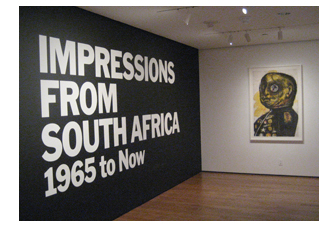

An alumna curator showcases works by South African printmakers—some never seen before in a US museum.

By Elizabeth Station

The Museum of Modern Art in New York City can overwhelm with its crush of tourists and massive, famous collection, especially in summer. Visitors looking for a different experience can escape to a small but powerful show organized by Judith Hecker, AM’97, assistant curator in the department of prints and illustrated books. Impressions from South Africa, 1965 to Now features contemporary prints by established and up-and-coming South African artists. They tackle serious themes—apartheid, torture, resistance, and reconciliation—using techniques from intaglio to linoleum cut. Hecker has worked at MoMA since completing Chicago’s Master of Arts Program in the Humanities. She talked about the exhibition during a recent interview at the museum.

What drew you to South African art, originally?

Because I didn’t do a PhD, I never had a particular niche. The advantage of being a generalist is that you get to curate across the century, and so I’ve done both historical and contemporary projects. Years ago I became interested in William Kentridge (b. 1955), who is probably South Africa’s best-known artist. MoMA did a major monographic show of his work in 2010 that was part of a touring exhibition. He works in many different mediums: theater, sculpture, drawing, film animation, and printmaking. I became really immersed and interested in his work.

How did that lead to building MoMA’s South African print collection?

Prints are created in such a way that there’s always more than one out there, unlike a unique painting, sculpture, or etching. And so the price point is lower, and we tend to collect more objects and take more risks, I think. We collected a lot of Kentridge’s work, and as I began to learn more about his career, I started to understand more of the context of printmaking and artistic production in South Africa generally. I took my first trip there in 2004. It was a great time to go because they were celebrating ten years of democracy since Nelson Mandela’s election. It was a terrific moment—all the museums were completely redefining their work and collecting more artwork by black Africans.

Where did you go on that first trip?

I visited Kentridge at his studio in Johannesburg, but I also went to many different provinces to research other artists and the role and prevalence of printmaking. I visited print workshops, universities, and community art centers in rural and urban areas. Printmaking is celebrated in South Africa in a way that's different from other countries. There are so many talented practitioners who aren’t well known either in or outside the country. So the trip was also an opportunity to bring new works into MoMA’s permanent collection, with an eye toward ultimately exhibiting some of the prints.

What’s the relationship between printmaking and politics?

What I wanted to illustrate with this show is how there are many different centers of production in South Africa, not just in the highbrow art world, because of the history and legacy of apartheid. There was a point when black artists couldn’t legally apply to colleges and universities, and they had to seek art training elsewhere. Printmaking was an especially accessible format that also had economic advantages—people could sell their prints and earn a living.

Wherever countries have undergone extraordinary political change, printmaking always plays a role. Mexico, Cuba, and South Africa are all examples. You can think back to Goya and Picasso too—there’s a strong link between printmaking and narratives about war, humanity, and cruelty. That’s part of the story with this show.

How have you continued to discover new artists?

I took another trip to South Africa in 2007, and since then I’ve stayed in touch with artists, publishers, and workshops. They’re constantly updating me on what’s being produced. The great thing about the print medium is that it’s not like shipping a sculpture or a painting—prints can be rolled up in a tube and mailed—so this has enabled me to continue acquiring works. Outside of South Africa, MoMA might now have the most holdings of prints by South African artists. At the same time, with this exhibition I felt really strongly about letting the artists be heard, so we brought some of them over to give presentations about their work.

Impressions from South Africa, 1965 to Now runs at the Museum of Modern Art in New York through August 29, 2011.

William Kentridge, General (engraving and watercolor, 1993).

August 18, 2011